Rembrandts Study of Italian Renaissance Art Was Done Mostly Through

THE SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN NETHERLANDS

Peter Paul Rubens (1577‑1640) Soon after he became a main painter in Antwerp, Peter Paul Rubens spent eight years (1600-1608) in Italy, where he copied in drawings all that he could come across of antiquarian and Renaissance art. Many artists earlier him made copies to tape the inventions of others and to absorb their style through the bailiwick of cartoon, but never to the extent that Rubens copied. Before his sojourn in Italy, Rubens himself had faithfully copied (in pen and ink) engravings by Holbein, Goltzius, and several other northern artists. In Italy, it shortly became Rubens'south life-long obsession to aggregate a paper museum, an anthology of classical art from aboriginal times and modern. For the residuum of his life, he used his drawings equally inspiration for his own fine art, or, as the seventeenth-century critic Roger de Piles put it, "to stir his claret and warm his genius." His drove drove his art. He kept his drawings in a cantoor, a cabinet or closet, in his studio where his own students could larn from them and work from them besides. Probably in the tardily 1620s, Willem Paneels and some other pupils copied more than than 500 of them, a collection now in Country Museum in Copenhagen.

4-27 Peter Paul Rubens, Copy after the Belvedere Torso, verso, ca. 1601-02. Red chalk heightened with white, 39.5 ten 26 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Rubens drew all the famous ancient sculpture then visible in Rome, including the Belvedere Torso (effigy 4-27), the Farnese Hercules, and the Apollo Belvedere. Nosotros know of over two hundred drawn copies of statues, reliefs, busts, gems, cameos, and more. He oftentimes drew famous pieces several times, from as many every bit six unlike angles. For example, he made over a dozen drawings of the whole and parts of the Laöcoon seen from different angles, including some unlikely foreshortened views. 5 or six of the original drawings of the group or its figures even so exist. In short, he treated ancient statues similar studio models who might be told to turn or strike a dissimilar pose for the master.

Rubens ordinarily rendered Roman sculpture in black chalk, but for a back view of the Belvedere Torso he used cerise, a color that approximates the appearance of flesh. (A black chalk drawing of the front view of the Body exists in Antwerp, Rubenshuis.) Like most of his copies of the antique, the drawing of the back seems highly finished and free of pentimenti, although the nighttime hatching around the torso would take obliterated any tentative preliminary lines. Rubens gave the nude body a narrower waist and more knotted muscles than the original marble. But he deviated from the original mainly past modeling the back with frail and softened hatching that mimics the subtler chiaroscuro of flesh rather than the harsh lights and darks of marble. His impulse to bring the statue to life also made him sketch a new caput for the torso.

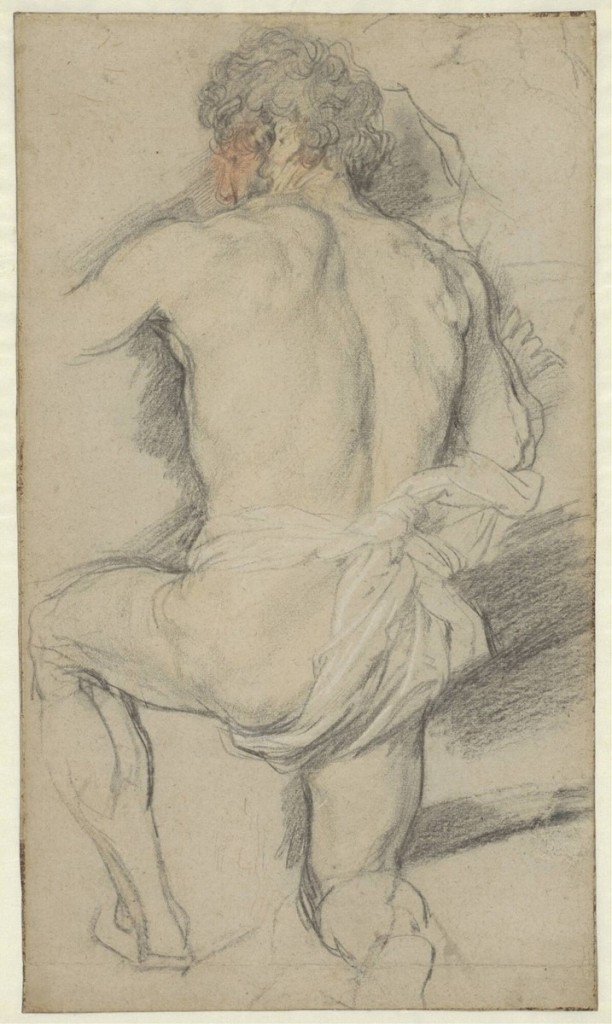

4-28 Peter Paul Rubens, Nude Youth Turning to the Right, after Michelangelo, ca. 1601-1602. Red chalk, 38.8 10 27.8 cm. British Museum, London.

In copying Renaissance art, Rubens favored artists working in the early decades of the sixteenth century: Polidoro da Caravaggio, Giulio Romano, and specially Raphael and Michelangelo. He normally used pen. Nevertheless, he made eight large, carefully rendered red and black chalk drawings of the prophets and sibyls of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, as well as a red chalk copy of one of the ignudi, Nude Youth Turning to the Correct (effigy four-28). As he did in his copies subsequently the antique, Rubens advisedly finished his rendition of Michelengelo's nude. He obviously wanted the cartoon to reflect the painting accurately for his own data base of Renaissance art. Nonetheless hither likewise he applied fragile modeling that gives greater definition to the muscles while imitating the texture of homo flesh. Rubens re-create looks more like the knotty anatomy of Michalangelo's drawings than information technology does the flaccid flesh of the ignudo in the fresco. Nigh thirty years later, Rubens made a counterproof of this cartoon by rubbing the back of it, transferring the design to some other sheet. He and then reworked this pale paradigm, now facing left, in a costless mode with a brush. The reversed ignudo somewhen became the figure of Bounty on Rubens's Whitehall ceiling in London.

In add-on to Rubens's ain copies of Renaissance fine art, he as well purchased a much greater quantity of copies drawn past other artists to take with him to Antwerp, and he occasionally hired artists in Italy to copy work for him. Over the years he did not hesitate to retouch several hundred of these drawings, usually a picayune, sometimes a lot, to bring them into conformity with his own style and suit them to his needs. He might apply opaque trunk color to obliterate lines and rework the whole, or he might paste on additional newspaper to extend a composition. Despite what we may retrieve of his habit of changing another artist's work, it underscores how essential these drawings were to his creativity.

4-29 Peter Paul Rubens, The Virgin and Kid Adored past Saints, late 1627-early 1628. Pen and brown ink, 39.five x 26 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Of the contemporary Italian artists working in Rome, Rubens had the greatest respect for Annibale Carracci. He paid Annibale the compliment of imitating not only his manner of drawing but also his design procedure. Annibale restored to drawing the essential creative role information technology had for Raphael: developing compositions through a series of drawings from primi pensieri to effigy studies and modelli. For many years Rubens adopted the same procedure. On the contrary of the sheet on which he drew the Dais Torso (effigy iv-27), twenty-six or 20-7 years later Rubens fabricated a quick sketch of his first ideas for the composition of his painting Virgin and Child Adored past Saints in Antwerp (effigy 4-29). He rapidly blocked out the majority of figures in pen with simple, faint outlines and and then began to adjust and darken the lines in the figures at top and bottom. Despite the vagueness of some figures and the reworking of others—the Madonna and Child announced twice—the massive figures display circuitous actions, and the emphatic spiraling blueprint of the painting is evident from the beginning. Sometime Flemish inventories called such quick pen sketches crabbelingen, scratches or scribbles. As he did in this sketch, Rubens usually made his primi pensieri in the fluid medium of pen and ink, often enhanced with brush and wash.

4-thirty Peter Paul Rubens, Kneeling Male Nude Seen from Behind, ca. 1609-x. Blackness chalk heightened with white, 52 10 39 cm. The Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Once the composition had been resolved in a modello, Rubens, similar Annibale, proceeded to draw studies of the model in blackness chalk to refine the pose, anatomy, and expression of the important figures. He made the study Kneeling Male Nude Seen from Behind (figure 4-30) to clarify one of the porters conveying treasure in the foreground of the painting Adoration of the Magi (Prado). Presumably, he used the services of a living model. Pentimenti effectually the periphery of the figure reveal how his eye searched for the exact contour that he so nailed down with a bolder line. He appears to have covered over an early contour on the far right with opaque white to requite the man a thicker waist and a more than powerful appearance. As Michelangelo had washed in his Libyan Sibyl (fig iii-14), Rubens redrew the leg which extended beyond the sheet. On other sheets, he frequently studied but the easily, feet, or head of a model. Clearly, the proportions and knotted muscles of Kneeling Male Nude come up directly from his copy of the Belvedere Torso. In drawing antique sculpture, Rubens converted marble into elastic flesh. When he drew the model, he gave him the proportions and physique of ancient sculpture. (He nearly never employed a female model.)

Rubens wrote virtually this 2-manner transformation in a minor treatise, De Imitatione Statuarum, "On the Imitation of Sculpture." In it, he highly recommends that an artist imitate ancient sculpture because, in the nowadays "degenerate" age, no one could find heroic models like those in antiquity. He has several reasons why a practiced model is nearly incommunicable to find. For i, the world is growing old, "decay'd and corrupted by a succession of and then many ages, vices, and accidents." (He believed that at that place was some truth in the fable of a Gilt Age.) However, he concludes that "the chief reason why men of our age are dissimilar from the ancients, is sloth, and want of exercise." Rubens goes on to extol the benefits of sweaty exercise with allusions to classical writers and with words that sound like an infomercial for a gym membership. Without adequate models, an artist must possess a thorough knowledge of antique statues, Rubens writes, so "that it may diffuse itself everywhere," every bit it did when he studied the model in figure four-30.

Nevertheless, when some artists imitate antique statues, they make their figures "crude, liny, strong, and of harsh beefcake." They "smell of the rock." Instead of copying the great many outlines, the sharp breaks, and the gloss of stone, artists should imitate the soft, diaphanous nature of flesh and the flexibility of skin which tin can expand and contract, particularly by observing the differences of light reflecting from stone and mankind. In curt, Rubens carefully considered the nature of imitation and had well-thought-out reasons for making men like heroic statues and statues like living men.

Shortly later his return from Italy, Rubens engaged a number of administration who helped him turn out a larger and larger body of painted work. No doubt he brought his studies of the nude model like figure iv-29 to a fair degree of finish and so that his assistants could use them to work upward a painting. But by 1620, Rubens was making very few studies later on the model, even though he began at that fourth dimension to produce large series of paintings for the ceiling of the Jesuit church building in Antwerp, for the life of Marie de'Medici, and for other projects. For example, only two or iii rapid compositional sketches exist for the Medici series of twenty-two paintings. To save time, his assistants undoubtedly used Rubens's enormous collection of drawings of classical and Renaissance figures and his own well-wrought, earlier studies of the model. Even so, in the 1630s, Rubens returned to a model when he drew nine or more large ruby and black chalk studies of the richly garmented figures in his Garden of Dearest, perhaps because of the unusual nature of the subject field matter. The prominent zigzag hatching of these drawings is quite dissimilar from the blended modeling of his nude studies twenty years before.

four-31 Peter Paul Rubens, St. Barbara Pursued by Her Father, 1620. Oil on Panel, 15 10 twenty.seven cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

As the number of figure studies and also compositional sketches on paper declined in the 1620s and 1630s, Rubens made more than and more oil-sketches on wooden panels. He sketched St. Barbara Pursued by Her Father (figure 4-31) in 1620 or 1621 in grooming for 1 of the thirty-nine ceiling panels commissioned for the Jesuit church building in Antwerp. This sketch, quickly drawn with a brush, using only 2 colors, possibly displays his offset thoughts for the composition—at least no scribbly crabbelingen for information technology, like figure iv-29, survives. For many oil sketches, Rubens first roughed out the design in chalk on the streaky dark-brown undercoat, or imprimatura. In the St. Barbara sketch, a few pentimenti tell us that he was withal uncertain nigh the placement of the arms. The two colors confronting the eye value of the imprimatura allowed Rubens to report the highlights and other lite and dark contrasts on the figures. On a larger panel, he later made a full-color modello of the design (now in the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London), which Van Dyck and other assistants subsequently painted on the concluding panel.

Of the approximately 450 oil sketches by Rubens that survive, most of them seem to be modelli presented to the patron for his or her approval. Artists had produced modelli in oil paint for generations. But some of Rubens's oil sketches, whether drawn past the castor with limited color, like figure 4-31, or painted in a number of colors, seem to be very early stages in the creative process, which other artists would usually accept rendered in chalk or ink on paper. By sketching direct in oil, Rubens apparently cut short the number of steps leading to the cease work. Preliminary oil sketches betoken he was superbly confident in his drawing skills and ability of invention.

Are they drawings? It is often impossible to tell merely from appearances the difference between his bozzetti in oil (first drafts or preliminary sketches) and his modelli in oil. Rubens and well-nigh everyone else in the early seventeenth century called all his oil sketches disegni (in Italian) or tekeningen (in Flemish), words that mean "drawings." He himself once coined the term "disegno colorito"—a phrase that combines the Tuscan tradition of line with the Venetian tradition of colour.

Rubens made several other types of drawings, including over forty title pages for books, many landscape motifs and animals, and numerous portraits. Rubens accustomed requests for portraits with bully reluctance, except from the aristocrats he courted as a diplomat. Their portrait heads were unremarkably studies for painted portraits. He most often caught the heads of his family, including his seven- or 8-yr old son Nicolaas (figure 4-32), for his own pleasure, not to start a painting. Every bit Goltzius did in his portrait of Giovanni da Bologna (figure two-29), Rubens enlivened the boy with red chalk for the face and contrasting black chalk for the hair—only without the showmanship of Goltzius's change of footstep from flashy hatching to intricate detail. Rubens's intimate portrait of his son is, for the most part, loosely fatigued except for the confront where delicate strokes of chalk render the smoothen skin of a child.

4-32 Peter Paul Rubens, Nicolaas Rubens Wearing a Blood-red Felt Cap, ca. 1625-27. Reddish, black, and white chalk, 29.2 10 23.two cm. Albertina, Vienna.

Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) Although trained past Hendrik van Balen, Anthony van Dyck and then thoroughly alloyed Rubens's mode of drawing that experts today sometimes accept trouble telling their drawings apart. Like Rubens, van Dyck learned past copying. In van Dyck's case, he attempted to sympathize Rubens by reproducing the bulk of the older artist'south "Pocket-Book." In his so-chosen Antwerp Sketchbook, the teen-age van Dyck copied figures from the "Pocket Volume"—figures that Rubens had copied from Italian and German engravings and from some paintings by Titian or copies of paintings by Titian. Van Dyck'due south Antwerp Sketchbook likewise contains pages well-nigh arithmetic, architecture, physiognomy, and other topics. Because of its clumsy way of drawing and deficient grasp of anatomy, some scholars accept rejected the attribution to van Dyck, although many drawings exhibit mannerism peculiar to van Dyck's later piece of work. Van Dyck himself soon rejected the broad range of learned interests (arithmetic, compages, . . .) that Rubens had pursued in his "Pocket Book" and in the remainder of his art.

iv-33 Anthony van Dyck, The Conveying of the Cross, ca. 1617-xviii. Black chalk with pen and dark-brown ink and brown launder, some white bodycolor on the robe of the Virgin, fifteen.9 x xx.5 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts (Wicar Collection), Lille.

By the age of nineteen, Anthony van Dyck, admired as "the best of his pupils," had became Rubens'southward chief assistant. While he worked alongside Rubens in his late teens and early on twenties, he painted a number of religious compositions on his own. For each of these projects, including The Carrying of the Cross (effigy 4-33), van Dyck dashed downward a series of first ideas, experimenting in every sketch with new characters, new movements, and new lighting. These drawings are characterized by bold lines in castor or pen and by strong contrasts of calorie-free and night. Seven compositional sketches for the painting The Taking of Christ exist, in addition to 5 sketches of figures. There are ten drawings for The Carrying of the Cross and half-dozen for The Crowning with Thorns. By repeatedly testing new possibilities, van Dyck fought to gain his own independence. He found his own way past working out intensely emotional interpretations of these religious subjects.

In The Conveying of the Cross, van Dyck reversed the direction of the procession toward Calvary from that of an earlier drawing in the series (at the Rhode Island School of Design). He made Christ'south head the focal point in the center of the canvas, while every line formed by most of the limbs and torsos thrusts up the hill along a diagonal to the right. The soldier's powerful arm and the nude back of a man throwing his weight forward are particularly emphatic movements. They all counter Christ'southward glance up to his sorrowing mother in the reverse management. As in other drawings in the serial, van Dyck began the cartoon with a preliminary sketch in blackness chalk, and so vigorously worked up the sketch with swift strokes of a pen and a brush filled with dark dark-brown ink made from gallnuts. (Rubens preferred ordinary bistre.) The patches of night emphasize the apartment planes of the figures, which are not modeled into solids by hatching, equally Rubens might have washed. Van Dyck had no fourth dimension for modest details similar easily or feet or for correct proportions—fifty-fifty at this early on engagement he tended to elongate limbs. He hunted merely for the emotional drive of the lines and the drama of light and dark.

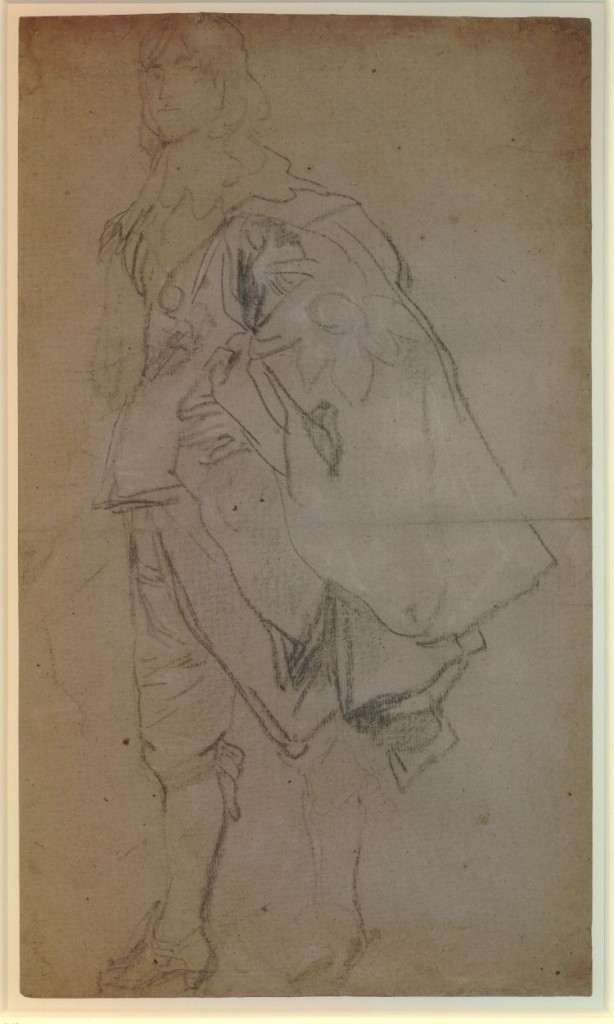

4-34 Anthony van Dyck, A Kneeling Man, Seen from Behind, 1618-21. Black, red, and yellow chalk, heightened with white. 46.3 x 27 cm. The Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

It was van Dyck's usual practice throughout his career to investigate farther some of the individual figures in his preliminary pen studies with finished chalk studies from the model. He drew A Kneeling Man, Seen from Behind (figure 4-34) in preparation for a figure in the foreground of the painting, The Crowning with Thorns (formerly Berlin). Van Dyck must have seen Rubens's similarly posed Kneeling Homo (figure 4-30), just van Dyck took a different approach. In dissimilarity to the dark modeling with white highlights by which Rubens exaggerated the model's muscles and majority, van Dyck concentrated on the contours of his figure. His modeling is light and the heightening is restricted to the loin cloth. (Another hand dabbed red and yellow chalk on the face.) Pentimenti on the right arm and left leg document his search for the appropriate lines. He repositioned the profile of the man's confront further to the left and, in the upper right of the sheet, he tried out other contours for the chest and shoulder of the homo. As usual, hands and feet practise non interest him. Whereas Rubens made his Kneeling Human being a piece of living sculpture, van Dyck's Kneeling Human being has more normal proportions and seems closer to the model. Characteristically, his drawing is flatter relative to Rubens'southward, and it avoids the allusion to antiquity that is and so typical of Rubens.

4-35 Anthony van Dyck, Copies after Titian and Annibale Carracci, Italian Sketchbook, page 21r. Black chalk, traced over by after hand in black ink, nineteen.ix x fifteen.4 cm. The British Museum, London.

But a few loose sheets accept survived from van Dyck'southward travels in Italy betwixt the autumn of 1621 and the autumn of 1627. Yet he was careful to carry back with him to Antwerp the 122 pages of a sketchbook he worked on effectually the time that he visited Venice (August/September, 1622). His Italian Sketchbook, at present in the British Museum, contains simply 4 preparatory studies, simply ii copies after the antique (How different from Rubens!), several copies of Renaissance and contemporary masters, and an overwhelming number of copies afterward Venetian artists, especially Titian.

He copied these works very freely, sometimes calculation notes about color, as an adjutant to think how the Italian artists had posed and lit their figures. He grouped the drawings according to diverse categories, every bit in figure 4-35, one of two pages he covered with scenes of the passion of Christ by Giorgione, Annibale Carracci, and Titian.He selected and combined motifs from the Italian Sketchbook in subsequent paintings in Italia, Flanders, and England. By drawing after Titian in his sketchbook, van Dyck captivated the Venetian artist into his blood. Years later, a glimpse at these sketches must have quickened his pulse.

4-36 Anthony van Dyck, Hendrik van Balen, between 1627 and 1632. Blackness chalk, 24.iii ten nineteen.8 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

Van Dyck made his reputation every bit a portrait painter, and many portrait drawings by him withal exist. Especially sensitive are the blackness chalk drawings of contemporary artists that van Dyck fabricated for the print serial The Iconography. In the portrait of his teacher, Hendrik van Balen (figure 4-36), van Dyck created a striking characterization of the human being.

On top of the intense dark hatching on his jacket sit his wisps of unruly hair, his (probably gray) bristles described with faint touches of chalk, his prominent bumpy nose and arched eyebrows, which frame ane eye focused on his former student and another eye that wanders. For a change, van Dyck elaborated the refined and sensitive hands of the older artist.

Considering of the demands on his time in England in the 1630s, he usually painted the head of a customer directly on the canvas in the sitter's presence, and so made workman-like chalk drawings for the costume and pose. Drawings such equally the preparatory report James Stuart, 4th Knuckles of Lennox (figure 4-37) were used by studio assistants to piece of work up the rest of the canvas.

1 sitter recorded that "with his grayness paper and black and white chalks, he drew the effigy and wearing apparel with a great flourish and exquisite taste for most a quarter of an hour." The strong black chalk lines in figure 4-37 also record van Dyck'south hand darting nigh the sheet, imparting life to the Duke'due south costume.

iv-37 Anthony van Dyck, James Stuart, 4th Duke of Lennox, ca. 1633. Black chalk with white chalk highlights on lite brown newspaper, 47.7 x 28 cm. The British Museum, London.

Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) When Rubens died in 1640 and Van Dyck died in 1641, Jacob Jordaens was already running the most important studio in Antwerp, comparable in size to Rubens's own facility. Jordaens employed six assistants and several apprentices in 1641. He had for many years adopted Rubens's style of drawing and followed his creative procedures that depended on drawing.

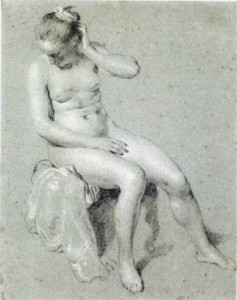

4-38 Jacob Jordaens, Female Nude Seen from the Back, ca. 1641. Blackness, red, and white chalk, 25.vii x 20.3 cm. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Most of Jordaens's 400 to 500 extant drawings are compositional sketches and more-finished modelli. He too fabricated chalk studies of heads full of character and chalk studies of the nude model from life, especially later on 1640, when his studio administration needed these designs to speed forth productivity. Female Nude Seen from the Back (figure 4-38) is a written report for a nymph milking Capricorn, i of the signs of the Zodiac, which busy a ceiling in his ain house. Jordaens liked to requite nudes, the female nude in particular, large swinging curves that create robust, rounded forms. Especially in the nude's thigh, nosotros can see his curved lines expanding the nude's majority as he coped with foreshortening a figure seen from beneath. The red contours he drew on summit of the black chalk correspond to the lines in the painting. Likewise, he modeled her back, legs, and artillery in a blend of crimson and black chalk, highlighted with white chalk. The combination of three chalks, usually reserved for portraits, has hither a hitting painterly effect.

4-39 Jacob Jordaens, The Peasant Family and the Satyr, ca. 1620. Pen and brown ink, brush and brown ink, 15.8 x 17.8 cm. Crocker Fine art Museum, Sacramento.

From the start, Jordaens drew compositional sketches in pen and ink and wash, commonly over a preliminary chalk sketch. In the 1620s, he savage sway to Caravaggio and his followers more than Rubens ever did. In Satyr and Peasants (figure 4-39), figures seen from a low bespeak of view fill up upward the foreground. The lantern above them makes patches of vivid lite and deep dark, which the artist set downwardly with a broad brush loaded with dark ink over broken, spontaneous contour lines in pen.

four-xl Jacob Jordaens, The Continence of Scipio, after 1636. Brush and dark-brown wash, torso color, 22.0 x 24.2 cm. The Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

A afterward cartoon, The Continence of Scipio (figure 4-40), illustrates a mutual characteristic of his compositional drawings of the 1630s and 1640s: the awarding of watercolor or gouache (body color) to the ink drawing. The coloring manifestly aided his assistants as they roughed out the design on a canvas. Jordaens based the composition of The Continence of Scipio on a lost painting by Ruben, every bit information technology appeared in an engraving. The drapery breaks in athwart folds, a characteristic of Jordaens's belatedly drawings.

THE NORTHERN NETHERLANDS

In the seventeenth century, almost Dutch artists specialized in a certain subjects, both in their painting and in their drawing. For instance, Hendrik Averkamp, famous for his paintings of winter scenes, also fabricated drawings of the frozen canals and rivers of The netherlands, likewise as lots of figure drawings of ordinary people. Paulus Potter and Albert Cuyp in their paintings and in their drawings focused on animals. Landscapists, of class, specialized in drawings of nature, just Nicolaes Berchem and many others also made sketches of shepherds and peasants—drawings they could utilize again and over again, sometimes reversed, to staff a hillside. Similarly, the genre painter Adrian van Ostade sketched figures to equip his tavern scenes. Balthasar van der Ast and other however life painters made precise drawings in watercolor and gouache of shells, flowers, birds, or insects. The marine painters, Willem van de Velde and his son, traveling with the Dutch and British navies, executed innumerable sketches of ships—from harbor scows to majestic warships. Pieter Saenredam, famous for his architectural interiors, usually started a painting with a freehand cartoon of the site. Later, in the studio, he worked out a measured rendition of the aforementioned view with straightedge and compass. Some important Dutch artists may take drawn very lilliputian. There are no drawings by Frans Hals or Jan Vermeer.

The majority of Dutch artists produced paintings for the open up market, instead of on commission. So too some Dutch artists fabricated drawings for the purpose of selling them to potential buyers. These were drawings not connected to the production of a painting and not part of the work-related stock of drawings kept in the studio. Collectors might place their drawings in an album or frame one of them and hang it on the wall. Averkamp, Adrien van Ostade, Cornelis Dusart, and several other Dutch artists often tinted their finished drawings with watercolor, probably to make them more saleable.

Perhaps more than other types of drawing, landscape drawing in the early seventeenth century contributed prominently to the development of the realistic character of Dutch art. Dutch landscape artists demonstrably based their faux of reality on the shut contact with nature fabricated possible through drawing. They traveled the countryside, making sketches of the distinctive ambling rivers, small forests, flat fields, and wavy dunes of The netherlands. The direct observation of nature, which cartoon immune, fostered a realistic approach in Dutch art for years to come up.

At the plow of the century, Hendrick Goltzius, who commonly produced fantastic mount vistas derived from Bruegel's Alpine prints, marked the start of something new with several realistic studies of copse, in brush and gouache, and two panoramas of Haarlem, in pen and ink. They are still bird's middle views, but their long flat horizon line captures the essential nature of The netherlands. Soon Claes Jansz. Visscher in Amsterdam and so Esaias van de Velde in Haarlem turned their back on the artificial conventions of mural that dominated the sixteenth century and led the way toward naturalism in their drawings. They were influenced by fourteen engravings made after drawings past the Main of the Minor Landscapes, published by Hieronymous Erect in 1559.

In 1612, Visscher published etched copies of these uncomplicated village scenes, attributing the designs to Bruegel. In the previous decade, Visscher was one of the first landscape artists in the northern Netherlands to make sketches from life, and in 1611 published an influential serial of twelve etchings of views near Haarlem in the aforementioned style.

4-41 Esaias van de Velde, Spaarnewoude, ca. 1615. Pen, brownish ink, and wash over traces of blackness chalk, viii.7 x 17.8 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Esaias van de Velde (ca. 1591-1630) Esaias van de Velde's drawing Spaarnewoude (effigy four-41), from the same period, illustrates the shocking freshness of simple and direct confrontation (quite different from Annibale Carracci'southward carefully arranged mural—figure four-7). As in so many Dutch landscapes, a road leading into the picture infinite invites the viewer to accompany van de Velde's three travelers on a walk. The foreground space—a continuation of the observer's infinite—lies completely open up. In the cartoon no coulisses artificially frame the scene; no alternating bands of light and nighttime prepare a contrived rhythm. The village lies nearly parallel to the film plane—the house on the left affords another diagonal toward the focal indicate of the church door. The sky is featureless, but a light wash on the buildings indicates late afternoon sunlight. Van de Velde's shorthand notation of rapid and abbreviated pen strokes is evidence that the artist sketched the scene from life. Spaarnewoude is the only preparatory study left for his etchings, Series of Ten Landscapes, published around 1615-16.

Jan van Goyen (1596-1656) In his earliest years, the prolific landscape painter Jan van Goyen imitated the pen and ink landscape style of his teacher, Esaias van de Velde. Nevertheless, in 1628 he took upwards black chalk every bit his but drawing tool and soon developed a personal style that he maintained for virtually thirty years of avid drawing action. Now and again, he stopped painting and started traveling. Some years he did almost nada just draw; other years he did virtually null but pigment. He seems to have needed direct contact with nature through cartoon to stimulate his imagination. Motifs from a drawing campaign 1 year would turn upwards in his paintings and in his finished drawings in subsequent years.

Among his more than than one chiliad drawings, five sketchbooks, which van Goyen certainly carried with him as he traveled, all the same survive. Two of them remain in their original status; the others tin can exist assembled from scattered drawings. A typical sketchbook held between 100 and 200 drawings, produced over ii or more campaigns. Van Goyen may take known that Esaias van de Velde, after he moved to The Hague in 1618, had compiled sketchbooks of chalk drawings. Dry chalk, perfect for travel, affords the landscapist a more rapid, more pliable, more nuanced, more than atmospheric medium than ink.

4-42 Jan van Goyen, House with Outbuildings and Copse on the Right Bank. Black chalk, 13 x 19 cm. Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

Business firm with Outbuildings and Trees on the Right Bank (figure four-42), from the sketchbook in Dresden, is a typical case of the kind of brief notations he made on his travels. It appears that he simply wanted to capture the motif of a farmhouse framed by trees, whose fluid lines are echoed in the wavy lines of the business firm every bit though both were one organic growth. Most sketchbook drawings are every bit hasty, fluid, figureless, and elementary, though observed with an experienced and keen centre. Back in his studio, he used Business firm with Outbuildings and Trees as the footing of a more finished drawing.

4-43 Jan van Goyen, A River Landscape, 1653. Black chalk and gray wash, framing lines in brown ink, xvi.eight x 26.eight cm. Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge.

Van Goyen created many of his chalk drawings every bit self-sufficient artworks that he sold in a serial, introduced in some cases by a titlepage. A River Landscape (figure four-43) must accept one time belonged to such a series. The cartoon all the same preserves its framing lines even though the margins were cutting away past a collector. Like the vast majority of his finished chalk drawings, van Goyen signed A River Landscape with his initials VG and the date, In 1653, his near prolific year as a draftsman, he produced near 250 drawings.

A River Landscape depicts a ramshackle grouping of buildings that slope toward the riverbank. A 6 people busy themselves along the river'due south edge. Van Goyen tended to include genre motifs in his drawings more than than most Dutch landscape artists did. Some of his early on drawings consist mostly of relatively large-scale, stiff figures in outdoor folk festivals and marketplace scenes, surrounded past a minimum of mural.

Fifty-fifty in a late finished drawing such as A River Mural, van Goyen handled chalk with a loose touch. He reproduced leafage with a flurry of lobes that tumble over one another as they explode upwardly. Long diagonal lines, punctuated with alternate bands of light and dark, atomic number 82 the eye toward pale gray horizon on the correct. He started calculation wash to his drawings six years before, in 1647. Launder configures clouds in the heaven, and streaks of launder in the foreground suggests that a low-cal cakewalk has ruffled the surface.

Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/29-1682) The bully landscape painter Jacob van Ruisdael had a variety of interests as a draftsman: woods, windmills, watermills, ruins, bridges, and more. Out of this mix in his 130 extant drawings, two distinctive kinds of drawings stand out. Ane group consists of well-nigh xxx large, elaborate drawings intended for auction. He usually began his finished drawings in black chalk, so brought out the foreground elements in pen, brush, and gray launder. As indications that they were made for auction, 2 of them are on parchment and several he tinted with watercolor.

4-44 Jacob van Ruisdael, Trees at the Edge of the River, ca. 1655. Blackness chalk, 14.5 10 19.one cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The other group consists of thirty small, quick studies of nature in black chalk, such as Trees at the Edge of the River (figure iv-44). None of his sketches were, strictly speaking, preparatory drawings for paintings or etchings. Still, many of them supplied the artist with motifs found in later work. Ruisdael may or may non have sketched Trees at the Edge of the River from nature. He was certainly capable of reproducing trees, water, and sky in convincing compositions from his imagination. Ruisdael'south diagonally receding riverbank resembles the blueprint of numerous river scenes by Van Goyen. Yet, Ruisdael had much less interest in genre and reduced the human being-made to one minor boat. What attracted Ruisdael was the thick, old oak tree clinging to the eroding riverbank, its dark lines silhouetted against the sky. He drew the limbs of this kind of tree with strong, short, flattened curves. The joints connecting the short curved lines form knobs along the gnarled old branches. He used an equally harsh zigzag line equally a autograph for foliage. His mode imparted to the tree in this drawing a heroic character.

Cornelis Poelenburch (ca. 1586-1667) A number of Dutch landscape artists in the seventeenth century traveled as immature men to Rome where they stayed for an extended period of study. Even afterwards they returned to Kingdom of the netherlands, these artists specialized in painting the rolling hills, ancient ruins, and rural life around the eternal city, based on the drawings they fabricated while in Italy. Cornelis Poelenburch was one of the outset of these artists to arrive in Italian republic (in 1617), and he seems to have been the first to develop a manner of drawing appropriate for the light and atmosphere of the southward. As we have seen, Claude Lorraine and Nicolas Poussin were aware of the work of Poelenburch and his compatriot Bartolomeus Breenberg.

iv-45 Cornelis Poelenburch, Interior of a Ruin with Figures, ca. 1621-23. Pen and chocolate-brown ink, brush and brown and gray ink, traces of blackness chalk, 42.7 x 38.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam.

As axiomatic in Interior of A Ruin with Figures (figure 4-45), the style is characterized past extensive use of brush and wash, which fashioned a landscape by means of a few stark, and as well many subtle, contrasts of calorie-free and dark. Areas of the sheet left blank become by contrast bright Italian sunlight. In this relatively nighttime cartoon, a small-scale-scale figure, dressed incongruously in classical garments, approaches what appears to exist the rima oris of a cave, but must in reality be a massive Roman arch, maybe on the Palatine. Poelenburch touched the cartoon here and there with pen to particular some leaf and rocks. The shadows and patches of light that ripple over the stones lend a curious aureola to the scene. Unfortunately, a later hand added some distracting gray wash in the lower left. The pucker that runs down the middle of the large canvass of paper indicates that Poelenbruch folded it for easy transport outdoors. At the aforementioned time that Bartolommeo Manfredi sparked a renewed interest in Caravaggio'south style, a Dutch artist in Italy demonstrated how to run into nature in terms of light and nighttime, rather than lines.

Rembrandt (1606-1669) When Rembrandt got into financial trouble in 1656 and had to auction the contents of his business firm and studio, an inventory was fabricated. The inventory listed twenty-4 books of drawings and two parcels of sketches, which he kept in the cupboards of his studio. Most of the drawings were systematically arranged between the blank pages of books according to subject: figure sketches, landscapes and views, nude men and women, animals, and i described as "A book spring in black leather with the best sketches past Rembrandt." Merely equally he arranged the drawings in his collection according to topics, so likewise he seems to have pursued drawing over the years according to certain themes—themes which today permit us to trace the evolution of his draftsmanship.

Despite his early on success as a portrait painter, Rembrandt fabricated only a few portrait drawings that were sold or given to others. He likewise made surprisingly few compositional studies or fifty-fifty preliminary studies of single figures and groups that were subsequently incorporated into his paintings or etchings. Both in function and in style Rembrandt'southward drawings were a far cry from drawings such as Annibale Carracci's An Angel Playing the Violin (figure 4-2).

Most often, Rembrandt designed the preliminary limerick on the panel or canvas itself. The relatively few studies that relate to paintings or etchings were usually variants of figures or groups, fabricated while he worked on the plate or canvas. Unlike Rubens, he never prepared a painting or carving with numerous drawings as Italian artists in the Renaissance and Baroque had done. Besides unlike Rubens, Rembrandt did not fill his drawing collection with copies of classical sculpture and Renaissance art. Although he endemic many reproductive engravings, his inventory listed only one "package of drawings from the antique past Rembrandt." Instead of preparatory studies, Rembrandt constantly drew the life around him, stimulating his imagination for biblical and historical characters with spontaneous and fresh drawings.

4-46 Rembrandt, Man Continuing with a Stick, ca. 1628-29. Black chalk, brush in white, 29.0 ten 17.0 cm. Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam.

At the start of his career in Leiden, near 1627, he began a series of drawings featuring poor people—the outset 3 sketched in cherry-red chalk, then about a year after, six more than in black chalk. Man Standing with a Stick (effigy iv-46) belongs to the second group. He drew the men presumably from life, only he also had in mind Jacques Callot'southward twenty-five etchings of beggars, Les Gueux (1623), in which Rembrandt could have seen plenty of long, vertical hatch marks. More concerned with capturing the image than with keeping the chalk sharp, Rembrandt used a rather edgeless piece of chalk—except for the darkest lines on the legs. And the relatively big sheet of paper immune his arm to gesture freely up and down the surface. As did many other artists, Rembrandt usually began a drawing with a faint preliminary sketch, and so he strengthened and adjusted it with darker lines. In this and many other cartoon, Rembrandt did not and then much adjust lines to refine a beautiful profile. Instead, he built the image predominantly with lines that are similar hatching lines. He evidently defined solids primarily by the contrast of light and dark rather than by outlines. The darkest lines on the back of the man'southward legs represent chiaroscuro rather than his final decision near a profile.

4-47 Rembrandt, One-time Human Seated in an Armchair, 1630-31. Scarlet and blackness chalk, 22.6 x fifteen.7. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

In his last years in Leiden, 1629‑31, Rembrandt did another grouping of drawings in the same media, blood-red and black chalk. For the mostly cerise chalk drawing Old Homo Seated in an Arm Chair (figure 4-47) and other drawings in the serial, he used the aforementioned model with his full beard, balding head, and wispy hair.

Rembrandt as usual began with a faint sketch of light lines, then fully filled in the habiliment and the large cast shadow behind the homo with a broad, diagonal application of chalk of middle value, and finally added the darkest and most powerful lines. They illustrate the freedom in drawing that immature Rembrandt had already acquired likewise every bit the strength of the gestures he used in drawing. Sunlight strikes the old human'south clasped easily and baldheaded caput, and dark shadows hide his eyes which seem lost in contemplation. In contrast to the rough and vigorous application of chalk, Rembrandt rendered the features of the head with some effeminateness. The combination of significant details with bold gestures in chalk or ink characterizes near all Rembrandt'south drawings.

In subsequent years Rembrandt adapted several of the drawings from these two series for figures in his paintings or etchings. Real people became for him the biblical characters. Life experience stimulated his imagination.

4-48 Rembrandt, Portrait of Saskia van Uylenburgh, 1633. Silverpoint on parchment, 18.5 x 10.7 cm. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

Shortly after he moved to Amsterdam, Rembrandt married Saskia van Uylenburgh,. To gloat their betrothal, he made a silverpoint portrait of her (figure 4-48). She wears a straw hat with a large brim and holds a flower in her hand. She is dressed equally a shepherdess, mayhap an allusion to pastoral love poetry. Silverpoint had all but disappeared as a drawing medium by this time. Rembrandt's use of it and the expensive sheet of parchment gave Saskia's portrait an air of something traditional or fifty-fifty old-fashioned. The delicacy of the silverpoint attests to her charm and to the happiness that Rembrandt plant in the idea of marrying Saskia. Even in the sketchy lines of her arms and shoulders, Rembrandt's touch is certain and certain. Soft shadows acquired past the hat veil her eyes.

Nearly the aforementioned fourth dimension, Rembrandt rendered his own features (figure four-49) in pen and ink and brush and wash. In Amsterdam, he preferred to utilise pen or brush and picked upward chalk less frequently. As a young man, in a serial of etched self-portraits, he made faces in the mirror to study how to render emotional expression.

four-49 Rembrandt, Self-portrait as an Artist, ca. 1633. Pen and ink, brown and white wash, 12.3 10 13.7 cm. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

Throughout his career, in many of his painted self-portraits, he dressed up and assumed a part, but the small number of self-portraits that he drew in pen or brush seem more straight frontwards and probably describe more than closely what he looked like as a working artist. His open shirt, wrinkled forehead, and the palette hanging on the wall tell us that he is professionally engaged. Yet if he were copying his image in a mirror, his blurred, active correct manus would be on our right, not on the left, as an ordinary observer would see it. In other words, he reversed what he saw, every bit he often did while carving. In the drawing, Rembrandt applied night launder to his jacket as though he were using strokes of pigment but covered the rear wall with transparent washes of very diluted ink. He very likely delineated his facial features, hair, and open up shirt with the tip of a pointed brush.

four-50 Rembrandt, Adult female with a Child Descending a Staircase, mid 1630s. Pen and wash, 18.7 x thirteen.2 cm. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

Shortly later Rembrandt's expiry, an artist-collector had in his possession a portfolio of 135 drawings representing the "Life of Women," more often than not scenes of mothers, grandmothers, and servants caring for children. The field of study clearly interested Rembrandt even though the inventory of 1656 did not list it equally a category. The drawing A Adult female Descending Stairs with a Kid (figure 4-50) was probably in that posthumous portfolio and maybe among Rembrandt's "all-time sketches" in the before inventory. The woman is not Saskia because her first three children died shortly after they were born, and Titus, who survived her, was born 8 months earlier she died of tuberculosis.

For these drawings of women Rembrandt employed mostly pen and ink, and as well brush and wash. The flexible quill pen allowed him to capture the constant motility and bustle of women and children around the business firm. No one could have posed descending stairs while carrying a child, nevertheless Rembrandt'south rapid strokes express the spontaneous movement perfectly. Several concluding emphatic lines—the bend of a knee, the flip of the skirt up the stairs—tell information technology all. The figures stand out against the light made stronger by the brownish launder on the right.

Drawings of woman'due south life appeared mostly in the late 1630s and early on 1640s, then petered out. The remarkable drawing, A Young Adult female Sleeping (Hendrickje Stoffles) (figure 4-51) is a tardily improver to the serial.

4-51 Rembrandt, A Young Woman Sleeping (Hendrickje Stoffels), ca. 1654. Castor and launder, 24.6 x 20.iii cm. The British Museum, London.

Hendrickje's bare leg suggests that she had been modeling in her husband's studio and, wrapping herself in a blanket, barbarous asleep from the boredom of posing. At that moment, Rembrandt grabbed a brush to capture her new pose. With wide, short strokes of scumbled ink, his brush slashed the sheet similar a sword. No matter the speed, every slash hit its mark sure and true. A big patch of gradually darkening launder, brushed diagonally toward her, hovers over her head like the weight of slumber itself.

During the 1640s and early on 1650s Rembrandt took long walks into the countryside surrounding Amsterdam and recorded in hundreds of drawings the farmhouses, waterways, and flat horizons of Holland. In brusque, he took up the Dutch tradition, popularized earlier in the century past Claes Jansz. Visscher and Esaias van de Velde, of illustrating the pleasant places and picturesque spots that urban center dwellers could visit on walks outside their city.

4-52 Rembrandt, The River Amstel at Kostverloren, late 1640s. Pen and wash, xiii.6 ten 24.7 cm. Chatsworth.

In The River Amstel at Kostverloren (figure 4-52), the lavish estate firm Kostverloren ("a waste material of coin") hides behind the trees. Two riders travel the towpath that ran along the river from Amsterdam to the house six kilometers away. Rembrandt whited out the two horizontal lines of the embankment in the middle foreground so that the perspective would sweep more than emphatically from the darkness on the correct to the afar horizon, which he indicated by simply a few dots and dashes. At some point he attached a strip of paper on the correct to add room for a clump of darker, taller trees. The billowing outlines of the trees, overlapping 1 another as they retreat into the distance, suggest a breeze in that management. With a few strokes of the pen and some light launder he created extensive space and a bright calorie-free diffused throughout the sky. Rembrandt's landscapes nearly never prove clouds. Whether he finished the landscape on the spot or in the studio, the vibrant touch of his pen gives the impression that he really experienced the scene.

four-53 Rembrandt, Christ Carrying the Cantankerous, mid 1630s. Pen and launder, 14.v x 26.0 cm. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

The majority of Rembrandt'south drawings, which the inventory listed but every bit sketches, depict figures or scenes from the Bible. Rembrandt drew one of them, Christ Conveying Cross (figure 4-53), during the 1630s, his most Baroque period. With a frenzy of pen lines he roughly suggested Christ groveling on his knees, Mary collapsing on the basis, John lurching forward to assist her, a holy woman racing to their aid, and some other woman falling backwards. A smudge of wash behind the stalk of the cross established a dark center effectually which all the activity swirls. With a few swift strokes of a broad dry out brush, he darkened the form of Simon of Cyrene, who carries an oar and a pail, to push the principal grouping back in space. Thick or sparse, his lines express movement and emotion more than they build solid bodies. Superficially, Rembrandt'due south excited pen lines resemble Guercino'due south penwork of fifteen years earlier (figure four-9), simply Guercino's pentimenti and arabesques do not actually construct emotion and drama every bit Rembrandt'south lines practice.

4-54 Rembrandt, The Mocking of Christ: Matthew 27:27-29, 1650/53. Pen and ink, fifteen.6 x 21.7 cm. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

Some years later, Rembrandt rendered another scene from the passion, The Mocking of Christ (figure four-54), this time with exceptional calm and classic equilibrium. For example, the hefty pillar on the right, at which Christ was disrobed and scourged, balances the two standing figures on the left. Christ and the 2 soldiers in effect mirror one another. The essential lines of the blueprint are nigh all horizontals and verticals; and forms have a block-like stability. Although Rembrandt used a small corporeality of hatching, he projected 3-dimensional infinite chiefly by thickening and concealment the lines of the foreground figures. The scene of mocking, which often in the past had a carnival atmosphere, has become static and quiet, a time for reflection.

4-55 Rembrandt, Hendrickje Stoffels Seated in a Window,

ca. 1655. Pen and wash, 16.2 x 17.4 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

In the tardily 1640s and throughout the 1650s, Rembrandt often picked up a reed pen instead of a quill. The wide, short, jagged lines in Hendrickje Stoffels Seated in a Window (effigy 4-55) betray the use of a reed. Since a reed pen holds trivial ink, the centers of its wide lines often run dry, as in the outline of Hendrickje's arm. No 1 will ever know why Rembrandt switched from a quill. Perhaps he liked the resistance that a reed pen offered: it hindered beautifying a cartoon with calligraphic flourishes. Or perchance he felt that a reed pen could imitate the marks of a paint brush. Many of his drawings, including this i, resemble his brushstrokes on canvas. Despite the differences between the drawings of an old human (figure 4-47) and Hendrickje's portrait thirty years later, Rembrandt was still attracted to someone sitting in the light, dreaming.

4-56 Rembrandt, Seated Female Nude, ca. 1660. Pen and ink, chocolate-brown and white wash, 21.1 x 17.4 cm. The Art Institute, Chicago.

Seated Female person Nude (effigy four-56) and a number of other drawings evidence that Rembrandt, at various times, drew from the nude model, male or female person. Using the same kind of pen, brush, and ink, his students studied the model with him—although from different angles—and made drawings markedly similar in style. In their drawings, they also employed a scratchy pen line and liberally applied transparent wash in the surface area around the figure. But in Seated Female Nude, Rembrandt's contours are fifty-fifty more indeterminate than his pupils'. In places like her hip and legs, they are peradventure as tentative and suggestive every bit the lines of his early Man Standing with a Stick (effigy iv-46). What distinguishes Rembrandt's drawing in this and in and so many other cases is the subtlety of the lite. His washes are expressive and suggestive, rather than descriptive of a value observed in nature. For example, the wash darkens behind her back to set up a stiff contrast with her white-washed body so that it gleams with light. In the large surface area on the right, he applied launder so sparingly that the space becomes transparent and seems to glow from inside. The strokes made by the castor, like rays of light, indicate to the woman who slumps in the glorious atmosphere. His washes accept little to do with the realism of cast shadows or modeling.

4-57 Jacob Capitalist, Seated Female Nude, ca. 1650. Black and white chalk on blue paper, 28.eight x 22.8 cm. The Maida and George Abrams Collection, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge. [not in scale]

Jacob Backer (1608-1651) Although no one has counted them, the Dutch probably fabricated more drawings of the living female nude that did artists in other European countries in the early seventeenth century. In the 1590s, Goltzius, Cornelis of Haarlem, and Karel van Mander made drawings "from life," presumably from the nude model. There are no other reports of life drawing in Holland until the 1640s, although a few Rembrandt nudes date from the 1630s. In 1648, Jacob Backer and Govert Flinck formed another university (kollegie), that is to say, a life class, for which they hired very probable ane of the Van Wullen sisters, who operated a bordello near Flink'due south studio. According to a contemporary document, she posed for Flinck equally "naked every bit possible." Capitalist drew his written report, Seated Female Nude (figure 4-57) and other effigy drawings in black chalk on blue paper. Blackness chalk of course lowers the tone of blue paper and white chalk raises it. The procedure resembles the style virtually artists of the menstruation adult figures on colored grounds in their paintings. Rembrandt almost never used colored paper—certainly never blue.

A portrait and history painter with classical tendencies, Capitalist drew only studies of the model, nigh all of them single figures, either nude or clothed. As in all his drawings, the contours of Seated Female Nude are clear, although not all that precise. Backer scattered highlights across her rounded forms—the outcome resembles a texture rather than a focused reflection of light. Vague touches of the chalks define the hair and the lost contour of the face. In that location are only a few cast shadows. Without the customary and arbitrary patches of dark behind the figure, she blends into the paper as into a soft mist. Her amuse and sensuousness had a special attraction for eighteenth-century collectors.

sarmientoencted97.blogspot.com

Source: https://historyofdrawing.com/?page_id=14

0 Response to "Rembrandts Study of Italian Renaissance Art Was Done Mostly Through"

Post a Comment